New Oregon Rules Protect Migrating Columbia Wild Steelhead and Salmon Within Cold Water Refugia

In 2020, The OR Fish & Wildlife Commission (OR Commission) adopted permanent angling regulations protecting migrating wild steelhead that rest in three critical cold-water refugia CWR) along the Columbia River – action long over-due but critically necessary and groundbreaking. TCA is grateful and applauds the Oregon Commission members – past and present – who made this happen.

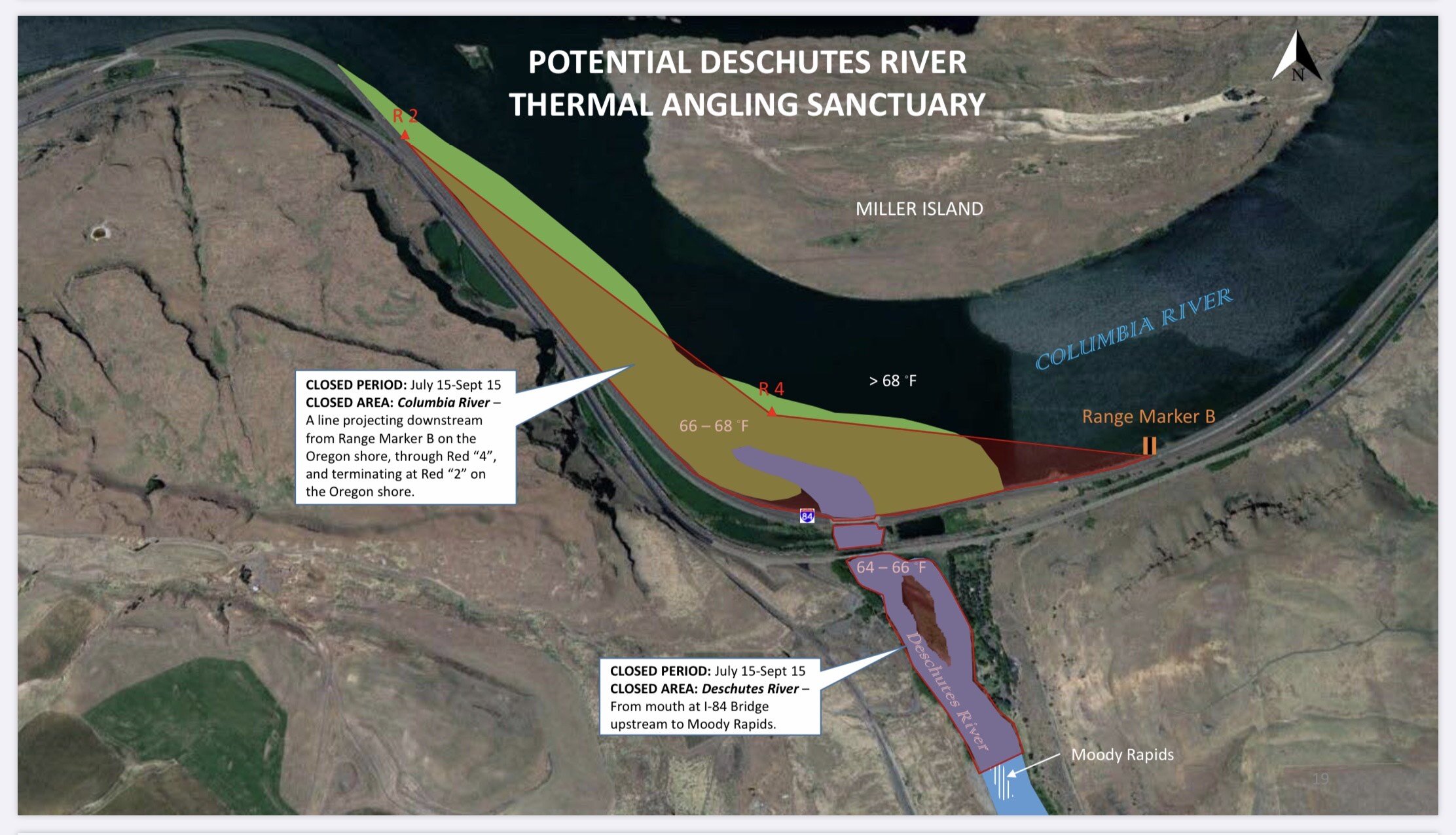

Facing warming water in the Columbia, rising above 68F each year in early July, migrating wild salmon and steelhead move into specific cold-water areas in order to avoid the physical stresses created by warm water and conserve energy for their migration and spawning once reaching their natal rivers. The OR Commission’s action in establishing sanctuary areas where ESA-listed salmonids are protected from angling encounters while they take up residence in cold water refugia will provide migratory survival benefits for wild steelhead returning to dozens of home water tributaries.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was required to review the impact of water temperatures on wild fish migration in the Columbia River as part of a legal settlement in a Clean Water Act lawsuit. The long-delayed EPA Draft CWR Report identified 191 water sources entering the Columbia mainstem between the Columbia River mouth and the Snake River. Thirty-five were warmer than the Columbia in July and August. However, EPA’s research and prioritization found twenty-three (23) significant cold-water refugia areas below the Snake River confluence. Based on the refined analysis on how wild salmon and steelhead used the CWR, EPA identified twelve (12) of these refugia as critical to wild salmon and steelhead migratory survival.

EPA’s research found that when the Columbia warms to 64F, salmon and steelhead begin to feel the effects of the warm water, and when the Columbia reaches 68F, every source of cooler water, regardless of size or volume, will provide refugia for migrating wild salmon and steelhead. Historic water temperature measurement data at Bonneville Dam indicate that the total warming of the river since the late 1930s in August (on average) is approximately 3.6F, rising from below 68F to near 71.6F. When wild steelhead and salmon encounter water warmer than 68F, migration becomes delayed, there are significant disease risks, increased stress and energy loss, significant sockeye mortality (ala 2015), and high concentrations of wild fish using the cold water refugia which presents a vulnerability to angling encounters.

EPA found that the presence, distribution, and water temperatures in the CWR within the Columbia River provide an advantage to migrating steelhead and salmon in terms of energy savings required to complete their migration, pre-spawn staging, and spawning. However, when the migration success of steelhead that used CWR versus those that did not use CWR was evaluated, that study found that migration success to spawning tributaries for those steelhead (wild and hatchery) using CWR was about 8% less than steelhead that did not use CWR. This initially suggests CWR use is not beneficial. However, the study also indicated that fishing pressure within CWR explained the decreased survival as wild steelhead using CWR, which must be released when caught, experienced a 4.5% decrease in survival during migration to their spawning tributaries compared to wild steelhead that did not use CWR.

The increased mortality is likely associated with catch and release mortality as well as the incidental catch of wild steelhead in tribal harvest fisheries. The fishing pressure within CWR makes it difficult to directly measure the benefits of CWR to migrating adult salmon and steelhead.

Exceptionally low wild steelhead returns since 2016 necessitate deep evaluations of angling impacts on migrating wild steelhead using the CWR. The OR Commission action establishing no-fishing sanctuaries are aimed to reduce the rate of wild steelhead encounters from fisheries (both indirect and direct) that have impacts on salmonid fitness, survival, and productivity. The three Thermal Angling Sanctuaries are at Eagle Creek, Herman Creek, and the very lower Deschutes River, and a portion of the Columbia River that is cooled by the Deschutes colder waters.

The Conservation Angler has advocated for these conservation measures along the Columbia since 2016 and supports the OR Commission’s adoption of these protective measures.

The Washington Commission must take the designation of thermal angling sanctuaries as well.